David Mac Laren: designer, maker, gallery founder

Words: Linda Nathan, Wood Review Editor

If we were to talk about significant people in the woodworking world of this country the name of David Mac Laren would figure extraordinarily large. That’s a realisation that tends to creep up, because he is a softly spoken and unassuming man who doesn’t push his ideas down anyone’s throat. Yet he has played a huge role in the lives and careers of many aspiring and well known woodworkers.

Thirty-five years ago David Mac Laren founded what must be one of the best galleries for fine wood in the world, let alone Australia, presenting the work of literally hundreds of makers.

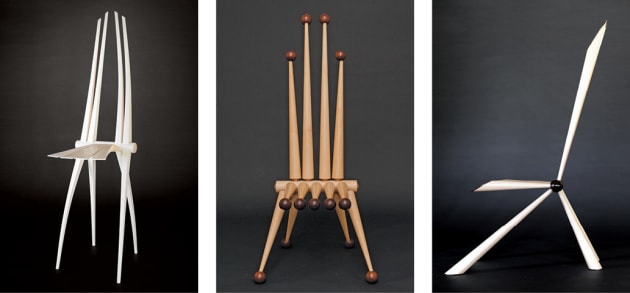

Above, left to right, furniture designed and made by David Mac Laren: Leda, 500 x 600 x 1850mm high, silver ash, Jester, 400 x 600 x 1650mm high, silver ash, jarrah, Strut, 400 x 650 x 1400mm high, silver ash, ebony. Photos: Stan D’Argeavel

If you chat to David it won’t be long before you hear him mention that failure is not something he generally worries about. There’s no bluster involved in saying that, and this attitude has obviously been one of the more liberating aspects of his life, because prior to opening the gallery he had already sampled quite a few life options.

Above: David Mac Laren, Stack, 1000 x 300 x 300mm high, natural and ebonised jarrah. Two structures that can be benches or low tables, or, when stacked, shelves. Joinery by Monaro Timbers. Photo: Stan D’Argeavel

Early on, in the late 1950s, David studied engineering at Yale, then took a year off but never went back. Wanting to broaden his education he chose to come to Australia, enrolling in an Arts degree at the ANU to study English literature and philosophy. In the early 60s he had to return to the States because of the Vietnam draft, but for medical reasons he ended up not getting conscripted. He stayed on in New York pursuing his then-dream of being a playwright.

In Manhattan there was a wood gallery that he would pass by and peer into with interest. Seeing a ‘help wanted’ sign out front triggered the next stage of his highly creative life. The furniture making studio in the gallery basement specialised in Nakashima and Wendell Castle knock-offs. Well it was the 70s after all, and the craft revival was in full swing—people were liking and making ‘natural’, earthy and handcrafted things.

In that studio a group of seven makers taught themselves and mentored each other. There were no formal tertiary courses in woodwork in the US (or in Australia) in those days. For David the studio was a fertile place where skills and aesthetics could be developed. One of the makers there had been a foreman in Nakashima’s workshop who had been poached by the studio owners. It was a time of slabs and stack laminated constructions that called for the reductionist methods that David still draws on in his work as a designer. In fact his first tools were electric chainsaws and grinders—‘I didn’t start with a sharp chisel’, he said.

Bunk Bed, 2100 x 700 x 2100mm high, silver ash, coolibah burl. Commissioned as one of a pair. ‘Ovalised’ rails and slats, and rounded posts made everything ‘soft’. Photo: Rob Little

A couple of years later David and a couple of the others set up a shared workshop in the lower East Side. These were hugely enjoyable times but eventually David and his Australian wife decided to return to Australia—it seemed like a better place to raise a family. Bungendore, not far from Canberra, was close to where they met at the ANU and that’s where they bought land to begin their organic, vegan, back-to-nature, self sufficient kind of life—well, it was the 70s after all.

Renting the corner store in town that reminded him of the Manhattan gallery was the start in 1983 of Bungendore Wood Works Gallery, even though it actually relocated to the corner opposite some ten years later. It wasn’t all about selling his own work; reaching out to other makers and creating a communal network was part of his ethos.

Left to right: Empire, 400 x 400 x 1700mm high, Asian High-rise, 400 x 400 x 1830mm, Gulf Tower, 400 x 400 x 1800mm, all in jarrah and burl. Photo: Rob Little

In the 80s the arrival of top flight woodworkers from different parts of the globe created a kind of woodworking ‘hotspot’ in the Canberra environs. In addition to David from the US, there was George Ingham, recruited to come here from the UK to found the Wood Workshop at the ANU’s School of Art. This would offer the first tertiary course of its kind in Australia, teaching high-end design and crafting in wood.

David Upfill-Brown (originally from South Africa) and Chris McIlhenney (UK), both graduates of John Makepeace’s Parnham House school also became part of a local scene of expatriate highly skilled designers and makers in wood. Rodney Hayward, a student of James Krenov with a PhD in chemistry was another who arrived from New Zealand in the mid-80s. (From 1999–2010 Rodney took over as director of the ANU Wood Workshop after George Ingham resigned due to illness.)

The first exhibition at the gallery came about after David gave eight makers each a quantity of American walnut and suggested they make a piece. David wonders if the work produced at that time has ever been matched for its fearlessness. ‘David Upfill-Brown made a corner cabinet that resembled a space capsule, he even made the hinges—who does that kind of work now?’, asked David.

No chainsaw went near the works in this exhibition but the idea of working down from a solid mass is still at the core of how David approaches design. ‘I’ve always felt the strategy of working with large section timbers and bringing them down made more sense than starting with small parts and going upwards. I’ve never been that comfortable with veneer work, or even steam bending. I guess my approach is almost sculptural, starting with Nakashima.’

Partial Ellipse, 1500 x 330 x 840mm high, jarrah, burl. The curved supports were cut from 45mm solid section. Photo: Stan D’Argeavel

Using solid timber is also central to his philosophy of how makers should consider handling what is increasingly becoming a moral dilemma for woodworkers—using a resource whose sustainability is in question. Veneers are widely regarded as an efficient way to maximise timber resources. Using veneer-faced substrates permits relatively fast furniture and architectural constructions with less likelihood of the problems associated with wood movement.

Yet David sees it another way. ‘My argument against using veneers is that we are trying to make the best use of our existing resource but at a very high cost of energy input. As veneers go down the manufacturing chain (you have to consider the substrate) they accumulate more energy, releasing more carbon into the atmosphere. So I conclude from that if we go back to using solid timber we’ll be forced to plant more trees, which is a good thing. Carbon accounting will sort this out.’

David also argues that the end-use of veneers is questionable. ‘The veneer I see used is for fairly trivial things, like at the airport: wenge veneers on toilet doors. And architects have over-used it, and often times it’s fashion-driven and will be dispensed with in 20 years.’ It can also be said that most wood is not being used to make high end furniture and art objects but instead for building and flooring, so perhaps woodworkers can assume less guilt, knowing they undertake some of the highest value conversion of precious timbers.

Because his gallery has presented the works of so many makers David has a unique knowledge of the standard of making in Australia, so it seems natural to ask him what his advice to other makers might be. Concentrating on finish and detailing is where he believes more energy should be spent. ‘Where I would put my best time and effort would be at the edges of furniture, because edges show your handwork. If you can create a non-machined edge that’s even better because if you spend an extra four hours on creating an edge by hand, that’s what will show.’

Seeing the reaction of buyers to makers’ work in the gallery also gives him insight into what people are looking for. Yes, he feels they are looking for a ‘style’, that speaks to them, but the way a maker develops a style needs to be an organic process that reflects the design solutions they come up with in response to their own evolving interests. Can trying to acquire a style be an almost artificial kind of thing for a maker? ‘It certainly can if you’re working from the outside in, I believe. If you’re flipping through books, I believe that’s the wrong way to go.’

Makers can at times underestimate how discriminating buyers of handmade furniture can be. ‘Oh they see everything and they’re pretty picky’, he said. ‘We’ve got clients that come in and they look under tables and see those metal clips instead of timber buttons, and they ask why. And I’m put in the position of saying: “Well some makers do that, and some don’t”. And I go back to the makers and tell them, but often they don’t want to hear that from me.’

The main issues in his mind that make woodwork more saleable are ‘detailing and finishing, certainly as the endgame. And the beginning game would be strategies for making, pricing and structure, and then some thinking about using veneers, using substrates. I think if people went back to using solid it would open up another box of goodies that people could explore. You’re up against the manufacturers, they can pop out veneer box-work very quickly, so for us it means looking into curved veneer work and vacuum presses as a way of distinguishing themselves from manufacturing. There’s a strategy to consider—how to accept the challenge of making one’s work more appealing or distinguishable from manufactured work.’

The way David Mac Laren talks about his various strategies gives a big clue as to how he has managed to found a gallery and grow it to the point of achieving international recognition, while continuing to develop as a designer maker. Likewise his lack of fear of experimenting with new ideas and structures has marked him as an innovator who has exerted a remarkable influence on Australia’s woodworking scene.

First printed in Australian Wood Review, issue 73, 2011

For more information on Bungendore Wood Works Gallery see bungendorewoodworks.com.au