Kevin Williams, musical instrument maker

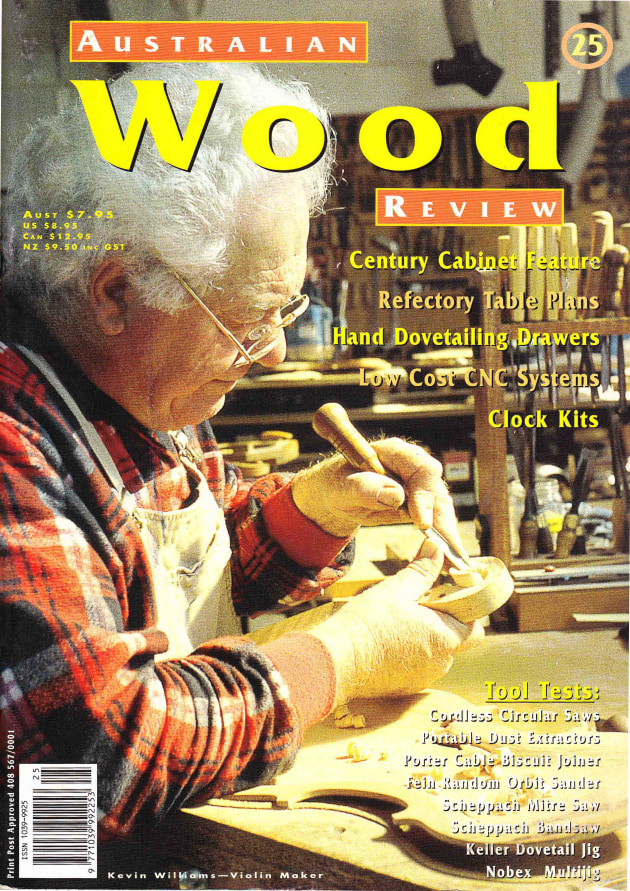

Kevin Williams in his Wooragee, Victoria workshop, circa 1999.

Words: Julie Turner

In the close, classical world of traditional violin making, Kevin Williams makes superb stringed instruments from Australian timbers, including mulga, acacias and King Billy pine – which makes him quite a rebel.

‘If I ever happen to meet Guaneri's ghost tapping tree trunks with a mallet in hand, well, we could sit down over a billy of tea and spin a yarn or two. Violin making would have taken a different turn if Tony Strad and Andy Guaneri and company had grown up in Australia.’

On a typical frosty morning in rural Wooragee in northern Victoria, Kevin and wife Lynne Iive and work surrounded by everything from finished instruments to logs awaiting break-down. Solid chunks of grain-rippled woods lie scattered throughout their airy home, collected from regular trips to the forests and deserts of the Australian bush.

‘Traditional makers don't usually get involved in the getting and breaking down of their wood,’ says Kevin. 'They don’t have the joy that l experience in going to the source and seeing the entire process through.’ Passionate about the textures, colours and sounds of Australian woods, he challenges tradition in exploring and advocating their use in musical instruments – not only violins, but guitars, harpsichords, pianos, lutes, harps and flutes.

A King Billy pine cello made by Kevin Williams

Crucial to his process over the years have been timber-getting excursions to many parts of Australia, including Gippsland, the Atherton Tablelands, the Otway Ranges, Pilliga scrub and the inland deserts: ‘Some of my happiest times have been spent in bush, outback or desert country or deep rainforest in search of timbers, obtaining the best possible materials from the source. It's an exciting experience to have been party to finding, felling, milling, seasoning and later transforming a piece of timber into a fine sounding instrument – with the added joy of playing it in a string quartet’.

Sometimes it means conning his way into cutting jobs in a forest, or into the mills. In the Otways he looks for fiddleback in messmate, manna gum, ash and blackwood. ‘You've got to make friends with the timber men,’ says Kevin. ‘They’re great blokes, straight as a die, no bullshit and trustworthy, and usually with tremendous stories to tell of the earlier days of their fathers and grandfathers, timbermen before them.’

In Tasmanian rainforest seeking King Billy pine, Kevin has fallen through horizontal scrub false forest floors of treacherous layers of interlaced fallen vines and detritus up to six feet high, forming hidden green grottos and caves: ‘If you fall, you hurl away your axe to save tearing yourself to shreds on the way down.’

At Strachan there’s an old-style mill run by notorious wild man ‘Cowboy Crane’. Kevin and daughter Alison joined the ‘mountain men of few words’ felling King Billy pines in the remote, rugged forest. The logs were brought out on an ancient timber jinker – a hair-raising trip on dangerously steep and narrow tracks: ‘We stopped now and then to tighten the brakes!’ Back at the mill, Cowboy (Bob) Crane threw a piece of chalk at Kevin: ‘Which bit do you want?’ He marked out quarter-cut flitches on the end of the massive log, then watched it pull into large twin saws, excited and privileged by the event.

Viola by Kevin Williams made from Wooragee red stringybark.

The quest has also taken him through the Flinders Ranges to the Eyre Pe ninsula, from Broken Hill to Tibooburra, camping near dramatic overhanging rocks, swimming in hidden pools beneath sacred Aboriginal cave paintings, in search of fallen dry land acacias.

On wood-seeking trips, Kevin feels it’s important to take examples of his work, which usually spark much interest. On a ten-day trip to the Eyre Peninsula in search of the western myall, the party stopped at a sheep station west of Port Augusta: ‘I ran into this lean, young bloke breaking in a horse. I told him why I was there, and showed him a viola. He said with surprise, “Did you make all that?” I spoke about western myall. “I know what you mean!”, he yelled, jumping on his motorbike, “Follow me!” We pursued him in a cloud of dust and he took us right to some fallen myalls. Saw an albino kangaroo on the way’.

Born in Broken Hill in 1925, Kevin spent his childhood exploring and bush walking his semi-desert surroundings. He developed an understanding of the symbiosis of animals, plants and trees on hands and knees in the soft earth, photographing tiny flowers, collecting botanical specimens for the local museum. He also attended brass band performances, watching his championship cornet-playing father conducting and playing, and accompanying Broken Hill’s silent films of the time.

Peter Williams, cello maker (left) with Jon Fedje, bow maker collecting western myall logs in the Eyre Peninsula.

At fifteen, Kevin was given a violin, and later chose to study at the Elder Conservatorium. It was at this time Kevin made his first violin, undertaking many research trips to Melbourne and Sydney to learn from the experts. He did various stints with both European and Australian luthiers including Adams and Smith in Sydney, and Sampson and Dolphin in Melbourne.

He later returned to Broken Hill to do apprenticeships in joinery and cabinetmaking, and later, building construction. Further theory work in botany and engineering drawing qualified him for technical teaching. Several years later, in a new Melbourne workshop, he turned his full attention to making and restoring instruments. Here he trained his son, Peter, and daughter, Alison, before moving to Wooragee in 1985 to work full-time on cellos, violas and violins.

His desire to explore the potential of Australian timbers began early. Traditional violin makers use only European maples and spruce, spending large sums on imported woods, ordered sight unseen. Dissatisfied with second best and the protracted delivery of imported timbers, Kevin’s experience in furniture making made him aware of the qualities of the Queensland maple which has roughly the same weight, density and working properties as European maple, making it suitable for the body of a violin. For the instrument’s front, he found an ideal counterpart to European spruce in light, highly resonant King Billy pine. Showing this first violin to members of the Adelaide Symphony with positive results, his passion for exploring the warm tones of native woods had begun.

Small violin makers planes are used to shape arched tops.

When beginning an instrument, he cuts the back and ribs of the violin from the same piece of timber at the same time ensuring a continuity of colour, texture and markings that are difficult to achieve with imported timber. He says traditional makers appear little concerned by the aesthetics of unmatched pieces. Favourite timbers of Kevin’s include Victorian messmate, alpine ash, mountain ash, blackwood and various acacias: twenty to thirty species have been explored so far, and there are many more to consider. ‘I won’t live long enough to complete this work.’

One unusual desert tree is used exclusively for the small, circular bushings for peg hole restoration work. The small, striking leopardwood tree has bark speckled with white, grey and orange patches, and yields an ideal and attractive, tight-grained wood. Tapered plugs are placed into peg holes and re-bored, leaving a fine, stable, delicately patterned ring in the refitted instrument.

Traditional makers import pale, almost colourless tonewoods which are stained the classical dark reds, oranges and browns. Often they’re ‘antique’d’ as well, with tiny pecks and scratches filled with stain, even artificial cracks and chips, maintaining the mythology of the old violin. By comparison, Kevin’s instruments feature the natural variety of Australia’s native timbers, from the delicate and subtle to the strikingly bold. Staining is unnecessary, and clear varnishes are used to create violins and cellos of red, brown, gold and yellow, glinting with the wood’s own textures and subtle hues.

A cello head by Peter Williams ‘emerging’ from Victorian ash.

Kevin creates handmade fittings for all his in struments, unlike other makers who use the dark metal, plastic and wood of standard, mass-produced imports. Fingerboard, saddle, chin-rest, tail-piece and pegs are crafted from desert acacias. Carved from perfectly matched pieces, their lighter chestnut or deep cherry-red gleam better complement the colours of Australian timbers.

He’s not averse to using machinery to ‘get the chips on the floor’ prior to the hand-finishing process. The front and back of an instrument is initially shaped with bandsaws, routers and an Arbortech powercarver. The ribs are bandsawn and precisely thicknessed with a home-made drum sander. For shaping the ribs, Kevin has also designed and built his own electric, thermostatically controlled heat bending machine.

He mixes his own oil spirit varnish using the gums and resins of native trees, based loosely on the old ‘copal carriage varnish’ previously used for horse-drawn carriages. Resins are dissolved in pure turpentine and ‘cooked’ in old iron pots. The essence is added to air-dried, washed linseed oil, and the varnished instrument is hung in early morning sunshine to absorb ultra violet light.

A red/brown varnish used in restoration work can be made from the resin of a native grass tree (Xanthorrhoea), a fern-like plant found in granite country such as Victoria's Warby Ranges. It exudes a rich, deep red gum into the soil, and is well known to Aboriginal people for melting around hand tools and spearheads.

Handcarved instrument scroll by Kevin Williams

With variations in varnish, handmade fittings and inlay decorations, no two instruments are similar (except a matched pair!). Each has an individual finish and its own warm, unique sound. These instruments are purposely not made thin, light and loud, as is a contemporary trend. Rather, they demand ‘solid work’ from the player, but in return give richer sounds and output: ‘You don’t get something for nothing’. In the past, Kevin has crafted several matched violins and violas from gleaming blackwood, messmate and Queensland maple, and aspires to creating an entire matched string quartet all from the same specially selected Australian tree.

This approach is seen as highly controversial in a tradition-laden craft whose roots trace back to medieval Europe, in particular Cremona, Italy, the ‘Holy Citadel of traditional makers’. There, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the famous Stradivari, Amati, Bergonzi and Guaneri families lived and worked, fiercely defending ‘precious trade secrets’, and cultivating a mythology which stands today. With violin auction prices now in six figures, Kevin knows the dealers of the world would keep it that way.

Kevin Williams and wife Lynne in their then-workshop in rural Wooragee in northern Victoria.

Although his instruments are played by musicians of note, including former principal cellists of Australia's major orchestras, and despite his work gracing the cover of the ultra-classical British Strad magazine, Kevin and his like-minded colleagues face strong prejudice against new instruments, especially those of non-traditional timbers. When players audition for European orchestras, the first question asked of them is, ‘What violin do you play?’ If it isn’t Stradivari, Guaneri, or at least antique, it’s notably sniffed at.

A cellist with a Williams instrument studying and performing in Europe, receives universally high feedback on craftsmanship and sound quality. ‘People either love it or hate it if it looks different from the Italian, French, English or German item. They may play it and say they like it, until informed that it’s made from Australian timber, whence they promptly put it down. The only “correct” timber comes from Europe.’ To Kevin this element goes beyond conservatism and mere tradition: ‘It's an intellectual thuggery perpetuated by dealers and auctioneers, for whom there’s no hefty commission on the sale of contemporary, new violins. The violin ‘mafia’ perpetuate the old mythology’.

Kevin has no beef with traditional timbers in themselves: ‘They make fine sounding instruments, and I respect the work of colleagues.’ He uses these woods in older restoration work, but is frustrated when makers, particularly in Australia, denounce Australian woods without having ever used them. ‘To continue to copy Cremona mindlessly seems to me to be a dead end, and without intelligent contribution to violin making, and to our arts in general. Would the art world accept endless copying of Da Vinci? Common sense would indicate that of the roughly 40,000 woody plants of the world, more than two species could possibly be considered for the making of musical instruments.’

Kevin Williams with Doug Cotterill, 1999

He has inspired several other instrument makers with his passion, including Warren Nolan-Fordham and David Brown, bow maker John Fedje, guitar maker Joe Gallacher, and harpsichord maker Alistair McAllister. Alison and Peter Williams have acquired broad skills in violin and cello making, and Doug Cotterill trained for six years in the Wooragee workshop. Recently Kevin assisted in acquiring some unusual redgum for distinctive grand piano maker, Wayne Stuart. These makers revel in their journey of passion and exploration.

Kevin Williams as he appeared on the cover of AWR#25

From memories of the brooding beauty of Mootwingee and Milparinka where, as Alison says, ‘the sky comes right down to the ground’, watching thunderstorms roll across great open plains falling through horizontal scrub and splitting open a block to discover, like Michelangelo, the unknown beauty within, Kevin's journey has been rich and exciting, full of delicate aesthetics and wonder. And this new direction for Australian makers has only just begun.

First published in Australian Wood Review, issue 25 (December, 1999).