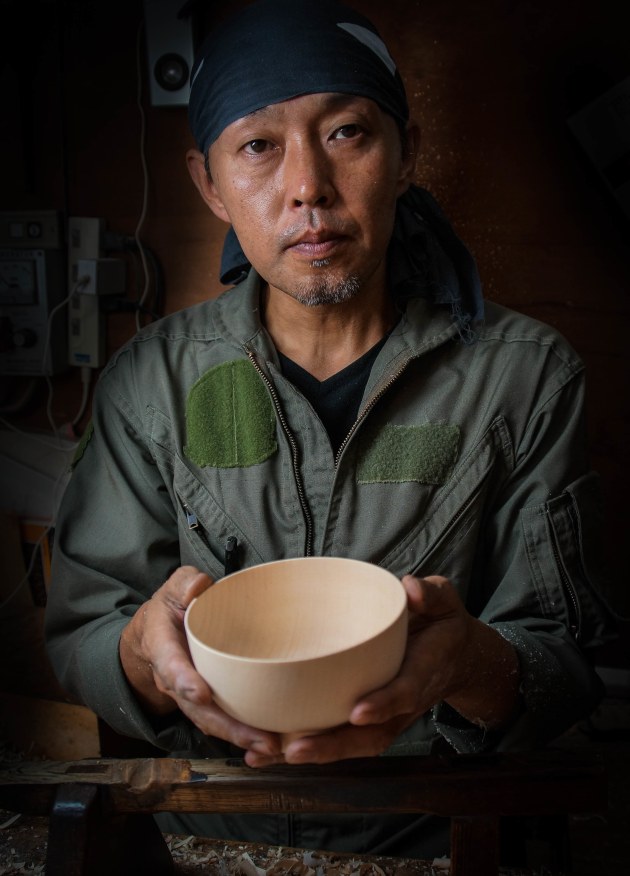

A Japanese Turner

Words: Yuriko Nagata and Terry Martin

Photos: Terry Martin

This story describes how one turner completes the turning of a bowl. Such bowls are probably the most commonly made turned objects in Japan. They may be used for rice, soup, or other dishes, and are usually lacquered, most commonly with a tinted lacquer that hides the wood beneath.

The region surrounding Yamanaka on the west coast of Japan is different from the rest of Japan because it is common for clear lacquer to be used so the wood beneath shows through.

Takehito Nakajima comes from a significant Yamanaka woodturning family. His father is Torao Nakajima, a recognised master highly respected for his kindness and commitment to helping others. Nakajima senior is a key player in the education of young turners. So it is not surprising that Takehito completed his own traditional apprenticeship with his father. He became an independent kijishi, or woodturner, at the age of 22, and in the 27 years since then he has himself become a craftsman of considerable standing in the community.

1. Pre-turned bowl blanks stacked for drying.

Lacquerware is one of the most highly prized products of Japanese culture and has reached a level of perfection unmatched in the world. A requirement for high quality lacquerware is that the wood must not warp after the lacquer is applied. This means that the wood drying processes are very sophisticated. All bowls are turned at least twice, and often they are turned three times before the wood is stable enough.

2. The pedals are used to select clockwise or anti-clockwise rotation.

The gradual release of moisture and tension in the wood is controlled by careful stacking so air circulates around the bowls in rooms where humidity is controlled (photo 1). In some places the partly finished blanks are stored in a room below where the turners work and they drop their shavings down a chute to be put in a slow-burning heater to slightly accelerate the drying process.

3. The pedals activate sliders that push the belts onto different pulleys.

In Yamanaka turners sit at 90° to the axis of rotation with the headstock on their left. The headstock is enormous with heavy bearings and a very thick shaft that ends in a hefty cup chuck. All work is either mounted directly into the cup chuck, or into a jam-fit chuck that is hammered into it. The lathe is driven by belts and often the motor is in a separate space so it is very quiet. The direction of spin is reversible and this is done by left and right foot pedals that move the drive belt onto counter-rotating pulleys on the main shaft (photos 2, 3, 4). When neither pedal is depressed the shaft does not turn.

4. Another view of the belt pulleys.

Like many Japanese turners, Nakajima-san sits in what is almost a cubicle, open on one side only. He sits against the ‘bed’ of the lathe, which is a flat table, and his legs are below the bed, positioned to operate the pedals. Nakajima-san forges his own tools, as do all Japanese turners, and he has an impressive array hanging on the wall ready for use (photo 5). These are mainly divided into hook tools and scrapers.

In the confined space it was impossible to take photographs from over Nakajima-san’s right shoulder, which would have given the best view of the tool as it cuts.

5. When you make your own tools, the possibilities are endless.

We watched the final turning sequence where he finishes a bowl that has already been turned once to dry. In normal practice each of the individual steps shown here would be repeated hundreds of times without changing the jam-fit chuck, but here he shows the process with just one bowl.

6. Mounting the blank in the jam-fit chuck.

In photo 6 we see a selection of jam-fit chucks at the back of his bench. He selects a suitable chuck and hammers

it into the cup chuck using the long cylindrical-headed hammer seen at the top of the photo. He hits it once hard and then rotates the piece slowly by gently touching a pedal so that it is not fully engaged.

As it rotates he rapidly aligns the blank with a series of small taps till it runs true. Then he quickly checks that the blank fits tightly in the chuck and adjusts with a quick cut of the tool if it is does not. The whole process takes less than a minute. The tools he will use are fanned out in front of him, each with a distinctive handle so he can identify them among the shavings. Between the tools and the hammer are four whetstones which he constantly uses to sharpen the tools with a quick flick of his wrist.

7. Turning the rim to size.

In photo 7 he trues the rim of the bowl, taking it down to the final external diameter and truing the internal diameter for rechucking. Like most Japanese turners, Nakajima-san does not measure, but he can make thousands of bowls, all with precisely the same dimensions.

8. Recutting the chuck to accept the rim of the bowl.

In photo 8 he has removed the blank and turns the jam-fit chuck down so it will accept the bowl blank in a reversed position. The blank is re-set on the chuck with a quick tap- tap, and in photo 9 he starts final shaping of the exterior of the bowl with a hook tool.

9. Shaping the outside.

His left arm strongly holds the tool rest on the table and his hand fixes the shaft of the tool in its fulcrum position. The tool handle is under his armpit, which counteracts the strong leverage of the tool due to the long overhang. He cuts with swinging sideways motions of his upper body – all with amazing speed and precision. You can see the small indentation in the tool rest worn by the tip of his index finger, the result of years and years of daily work.

10. Final cutting of the foot.

In photo 10 the outside is completed by defining the sharp division between the bowl and its foot. How clearly his two index fingers define the axes of his movement! The whole outside is turned in less than a minute.

11. Scraping the exterior.

The final outside touch is made in photo 11 with a hand- held scraper made from a piece of bandsaw blade taped to

a piece of bamboo for support. It is always sharpened with a quick flick on the whetstone before use. The shavings seems to melt off the wood and it is done in seconds – no sanding required.

12. Selecting a chuck for reversing the blank again.

Nakajima-san selects another jam-fit chuck for turning the inside of the bowl in photo 12. Tap-tap, it is set up and the interior is turned in photo 13.

13. Turning the inside.

He has moved the tool rest across to the front of the bowl and it is finished inside with a few quick swings of the hook tool. In photo 14 the curved end of the scraper is used to finish the interior with a jet of perfect shavings.

14. Scraping the interior.

Finally, Nakajima-san holds up the bowl and his expression says, ‘I made this’. It all happened so fast it was hard to photograph, but when he is in proper production mode doing each step hundreds of times without changing chucks, it would be even faster. So we asked, ‘How many of these can you make in a day?’ He quietly answered, ‘Two hundred.’

Yuriko Nagata is a researcher with the University of Queensland.

Terry Martin is a Brisbane-based wood artist, author and curator, see www.terrymartinwoodartist.com