A box project: recycled, bleached and scorched

1. Andrew Potocnik’s finished fingerjointed box made from recycled oak pallet timber.

Words and photos: Andrew Potocnik

In a world where profits rule, it’s often cheaper to throw things away than re-use them. This is the case with pallets used to transport products around the world, which at one stage they gave rise to a genre of furniture and fitouts.

Here, I started with two pallets and shaved back the weathered outer surfaces down to identify ash, maple and possibly pin oak. Much of this wood contained cracks and distorted grain, and one idea I had was to incorporate heavily burnt and cracked endgrain slices to create a landscape effect on the lids.

Before marking out sections for boxes like the one shown above I ‘read’ the wood as best I could. I ripped the timber down to a thickness of about 9mm on a tablesaw, and put it aside for a number of weeks to settle and see whether there would be any distortion before thicknessing to about 6mm. Fortunately most of it stayed flat, so I could cut and plane it to widths of about 70mm, then dock to length.

2. Docking sides to length on the mitre saw.

3. Using the Rockler fingerjointing jig is straightforward. The ends of the joints were cut slightly overlength to trim back to a neat fit.

With overall dimensions determined, timber was cut to length on a drop saw (photo 2), then it was time to cut

joints. It took a matter of minutes to cut all joints on the router table using a Rockler fingerjoint jig (photo 3).

4. Sides jointed. Inside and outside faces were selected and labelled beforehand.

Laying all parts out in sequence (photo 4) makes the process fool-proof; but best of all, the joints fitted neatly and tightly, with a small amount of protruding material on each of the fingers – something you can do away with depending on how you set the jig up. I just wanted a bit of excess for security’s sake.

Grooves were next routed for the lid and base panels at the top and bottom edges of each side and end piece of the box. I set up a router table fitted with a 3mm cutter and set the fence to the same distance from the top and bottom edge of the box. A groove was made in all pieces, keeping in mind not to cut beyond the reach of long edge fingers.

5. Grooving the sides on the router table for the lid and base panels.

An entry and exit point of the cutter’s reach was marked so I didn’t start the cut too early, or end it too late (photo 5). It’s difficult to explain, but I needed to ‘drop’ wood onto the cutter to begin the groove and switch the router off at the end of the cut before lifting each piece off the router table. Safety is the key point here, even if it takes a few seconds longer.

6. The grooves were lightly sanded for a smooth fit.

Once routed, all grooves were eased with sandpaper to ensure easy fitting of panels, and to remove any rough edges (photo 6).

7. Floating panels for the base and lid were trimmed to size on the drop saw.

Top and bottom panels, machined to 3mm, were cut to size (photo 7), allowing for a little cross-grain expansion in the slots. These ‘floating panels’ are not intended to be glued all around and fight timber movement. Even though these panels were machined to match widths of the grooves, they were still to be sanded which would reduce thickness another couple of woofteenths, so the fit wouldn’t be too tight in the final assembly.

8. Pre-finishing before assembly gives better results.

I like to pre-finish all components before assembly in stages as required, hence a wipe on-wipe off application of polyurethane was used (photo 8) before moving onto the 3mm lid insert which I bleached to contrast with the burnt plant-ons.

9. The lid was bleached so the scorched decoration would contrast even more.

This was a two stage process and I carefully followed the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure a safe and suitable outcome (photo 9). The top surface was left raw and the underside was also finished with a wipe-on, wipe-off application of polyurethane.

10. I purposely picked the worst bit of pallet wood for the pieces to be torched.

Our timber is precious and should be celebrated, not wasted so with the motif that would go on the lid I aimed to make a statement about our landscape and the timber we see as being ‘useless’. Hence I searched for the most degraded and cracked piece of wood in my stock (photo 10), bound outer edges tightly with masking tape and cut a series of 5mm slices on a drop saw (photo 11).

11. Edges were taped before dropsawing against my made-up stock block jig.

Beware! In this case I set up an MDF support with an attached stop-block, but after every pass of the blade I allowed the saw to stop spinning before raising it so the spinning blade didn’t flick the slice into the outer regions of my workspace.

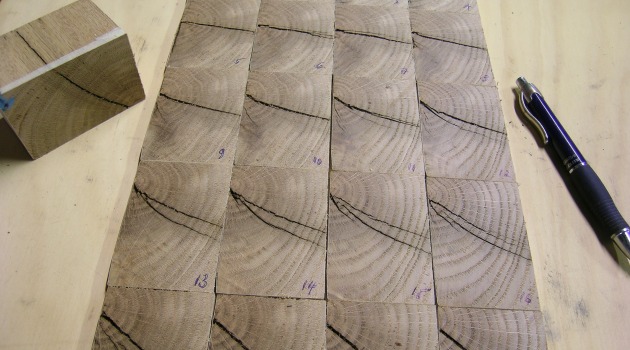

12. I cut more endgrain pieces than needed, then played around to select the best arrangement.

I cut far too many slices (photo 12), but this gave me the opportunity to find the most appropriate combination.

13. With everything ready and fit checked, glue-up went smoothly.

At this point I moved to assembling the box, gluing all parts together with PVA glue (photo 13) and a few clamps just to ensure all parts fitted correctly. The jig will ensure joints fit tightly and accurately, so you can almost do away with clamps on a small scale project such as this...but be sure all joints meet neatly and at right angles before letting glue set.

14. A flush-trim bit on the router table trimmed the fingerjoints neat.

The fingers I had intentionally left a little too long were next trimmed with a flush-trim bit on the router table – note the use of a pushblock to keep fingers well clear of the cutter (photo 14). A little hand sanding finished things off.

15. A gas torch was used to char the pieces evenly.

Now it was time to prepare the pieces of the cracked ‘landscape’. These were heavily burnt with a gas torch (photo 15) to remove softer parts of grain and allow harder growth rings to remain.

16. Wire brushing removed the softer growth rings and loose charcoal.

Once these charred areas had been wire-brushed away they would tell their story of how the tree had grown (photo 16). These were trimmed with the help of a spacer to leave even spaces between top and bottom edges.

17. Spacers helped position the charred sections as they were glued on.

The raw edges were burnt before all the pieces were ready to be glued into final position with thick gap filling glue (photo 17).

18. Sawing the lid off on a pedestal drill.

You can separate box tops and lids on the bandsaw, tablesaw, by hand or as I did by using a 500mm dia sawblade fitted to an arbor on my pedestal drill. This was lowered to the desired height, using a piece of scrap to protect the box sides from the arbor (photo 18).

19. Flushing off the lid on a sanding board for a square fit.

I left a small amount of wood intact on each corner to prevent the sawblade removing more timber than I wanted. This was cut away with a handsaw and all cut surfaces cleaned up on a sanding board (photo 19), so both top and base met as neatly as possible.

20. Gluing in filets to act as lid stays.

There are many ways to fit lids, and to be truly honest I detest fitting hinges so I opted for a couple of 2mm thick pieces

of wood glued to the inner edges of the lid. These would protrude 4–5mm and slide into the top section of the box for a neat fit. The filets were pre-finished and their corners eased slightly before gluing them into place with a couple of spring clamps (photo 20).

Using recycled wood is a commendable but not necessarily a cost effective process. Breaking down pallets, removing nails, sorting through and matching the pieces all takes time. However it can fire your creativity as it is a process driven by the heart, not the pocket, and the rewards can be wonderful.

Andrew Potocnik is a wood artist and woodwork teacher who lives in Melbourne. Learn more at www.andrewpotocnik.com