Masterpiece Cabinets, Part 1

A three-part feature draws together the work of three makers who all live in Australia, but thousands of kilometres apart. Each has designed and crafted a cabinet of extraordinary merit that has recently received awards. What ties them together is the level of excellence, complexity and attention to fine detail their work presents. Each acknowledges the profound influence of the past makers, traditions and styles they have researched. While referencing the past each piece is an original design, created as a tribute to those traditions, and for the enjoyment of the technical challenges they presented. First presented in our series is the Curiosity Cabinet made by Martin Burgoyne, West Australia, who describes the intricacies of his prize-winning cabinet below.

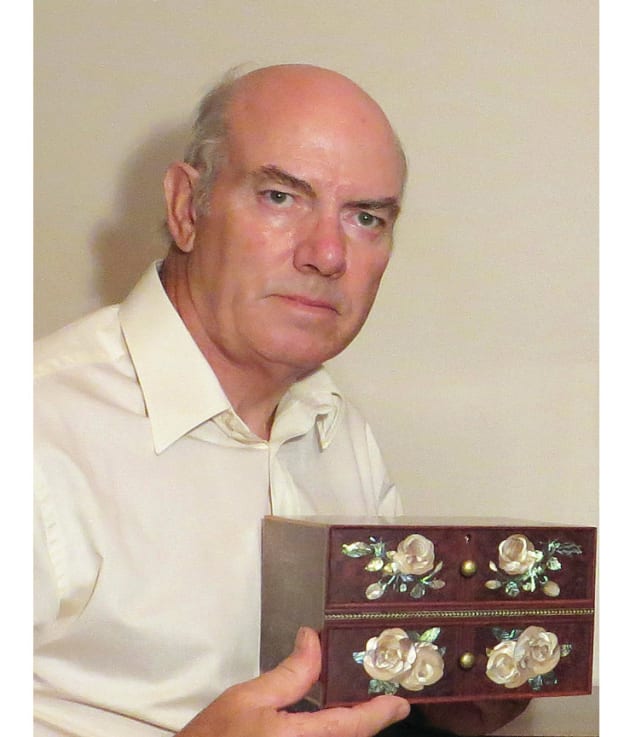

Words and photos: Martin Burgoyne

I have always been amazed at the delicate, complicated and intricate work of 17th and 18th century cabinetmakers. Their work has inspired a number of my projects during the last few years of my retirement. Research led me to the curiosity, table and collector’s cabinets of this period. With their complexity, myriad small drawers, secret compartments, and extensive inlay —

I just had to make one! So the concept of Ancient and Modern was born.

The more I researched these old cabinets the more ideas for secret hidden compartments I found. I just had to build some in — 16 to be precise, which in turn hold another 28 small drawers. Most of these old cabinets also had a central ‘theatre’ — more scope for marquetry, parquetry and inlay.

Above: Martin Burgoyne, Ancient and Modern, 640mm wide x 410mm high x 280mm deep. Jarrah veneered marine plywood, solid jarrah, various species for marquetry and inlay. Photo: Martin Burgoyne.

Some of the 12 main drawers in the cabinet were fitted out for a range of traditional games — yet another opportunity for inlay. So a combined chess and backgammon board, a cribbage board, and a double-sided Chinese chess and Nine Men Morris board were added.

Most secret compartments are concealed behind a series of false backs. The Secret Box is disguised as two of the main drawers in the cabinet; once removed it gives access to a false back. This false back is removed using a special ‘key’, giving access to one of the secret compartments with its four small drawers. In fact the removal of each of the other seven main drawers gives access to the rest of the false backs, in some cases after a complex sequence of moves.

The special key is actually a small block of wood in which two rare earth magnets are embedded. These in turn are attracted to more magnets in the false backs which can then be lifted or slid to one side to enable them to be removed. As the magnets' poles are set in opposite ways, a number of combinations are available for ‘attaching’ the key to the false backs.

The central theatre provided scope for more marquetry on the inside of its doors, and a range of parquetry on its floor, steps and ceiling. Three small treasure chests are contained within the theatre hidden behind another small central doorway with its marquetry perspective scene. With the treasure chests removed, access is gained to another false back and secret compartment with three small drawers.

However gaining access to the treasure chests and then the false back requires a number of other elements to be removed in correct sequence. The two different marquetry pictures on the inside of the doors are made from 1.5mm veneer cut with a fretsaw and are based on furniture designed by Jean-Henri Riesener in the 1780s.

The shell motifs for the drawer fronts were let into holes cut into pieces of 1.7mm thick bookmatched jarrah veneer. The assembled sheet was then glued onto the drawer front, with a cockbead providing the finishing touch. The left and right hand shell inlays were made to order by a luthiery supplier.

The Secret Box was the last element to be made, and making it fit into its space in the cabinet was the most exacting part of the whole project. Drawers made slightly oversize from solid timber can easily be sanded to fit their openings, but a veneered box cannot be sanded to fit so real precision was required. Barrel hinges were used for the lid so there were no knuckles to get in the way as the box slid into its opening.

Making the cabinet kept me quiet for just over a year. After my first marquetry clock I said I wouldn’t do another, it was just too complicated. I’ve said the same about Ancient and Modern but who knows!

Facts and figures

Hours spent:

Joint types: Through and lapped dovetails, stopped housing joints, corners joined with a drawer lock router bit

Number of joints: 152 handcut dovetails, including 76 lapped, 58 housing

Inlay: 40 metres of inlay stringing, bandings and boxwood corners, 18 shell motifs

Components: 54, including 38 drawers, 5 boxes, 5 doors

Marquetry pieces: ‘Thousands’

Secret compartments: 11

Moves to access all parts: 18

Species: 27, applied mainly over veneered marine ply

Power tools used: 5

Hand tools: 45

Mistakes made: too many to remember, but no remaking needed!

Ancient and Modern won three prizes at the Perth Wood Show in August 2013, and The Secret Box won an AWR’s Boxmaker 2014 award, see AWR#83. Martin Burgoyne taught woodwork and design technology for over 20 years in the UK, before retiring to Jarrahdale, WA in 2006.

Reprinted from Australian Wood Review magazine, issue 85.